Most discussions around core.async, be it in Clojure or ClojureScript, tend to focus around the key concepts of the library - specifically chans and the go/go-loop macros. This isn't a bad thing as that is were the power of the library comes from, on the other hand core.async also has a few powerful higher-level features that let you do some very interesting things and they deserve a bit of love as well.

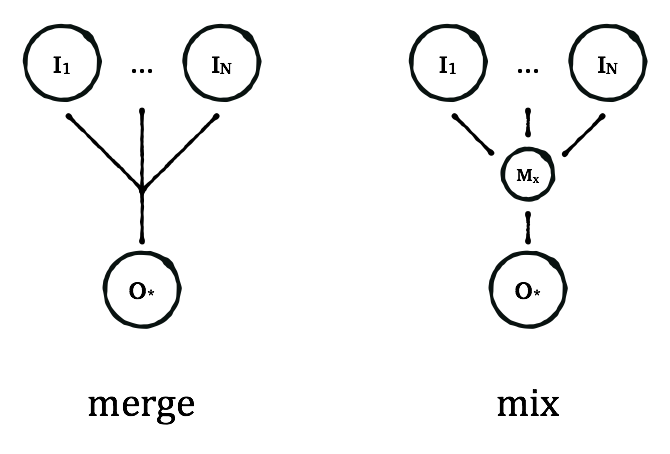

Two such features are merge and mix. Both methods have a similar goal - combining multiple input channels into a single output channel however in practise they are rather different.

At a high level you could draw the 2 operations like so,

In fact the mix diagram is slightly more complicated in reality but we can expand on that as we go.

Setting up

So lets look at some examples of these operations. I'm talking in the context of ClojureScript in this case but same reules and principles apply in plain Clojure.

If you want to try these examples and are rather new to ClojureScript I recently outlined a basic ClojureScript setup which will get you up and running.

Assuming you have an empty ClojureScript project one way or another you need to add a reference to core.async in the :dependencies section of the projects project.clj

:dependencies [[org.clojure/clojurescript "0.0-2173"]

[org.clojure/core.async "0.1.303.0-886421-alpha"]]

Then in your ClojureScript source (probably src/<project_name>/core.cljs) you need to import a few things. I'll assume you have at least a basic understanding of channels and core.async already so we can just import everything we need for the examples.

(ns chat.core

(:require [cljs.core.async :refer [mix admix toggle merge chan <! >! timeout]])

(:require-macros [cljs.core.async.macros :refer [go]]))

Now we are about ready for the examples.

merge

merge is the simpler of the two features and as the API documentation says combines 1..N source channels and returns a channel which contains all values taken from them. The operation is entirely immutable. That is, once you use merge to create a channel you can't add or remove channels later. When all input channels have closed the merged channel will also close.

This is useful when you have multiple event streams, represented as channels, and you want to process them in the same way and in a centralised manner e.g. when you are wanting to parse multiple simultaneous server requests, web socket events or user interactions from various parts of the user interface.

To keep the example simple we will just create 3 channels that randomly publish their names every now and then,

; declare the channels

(def in-channel-one (chan))

(def in-channel-two (chan))

(def in-channel-three (chan))

; define the function for publishing

(defn randomly-constantly

"Constantly publishes the given value to the given channel in random

intervals every 0-5 seconds."

[channel publish-value]

(go (loop []

(<! (timeout (* 1000 (rand-int 5))))

(>! channel publish-value)

(recur))))

; start putting stuff on the channels

(randomly-constantly in-channel-one "channel-one")

(randomly-constantly in-channel-two "channel-two")

(randomly-constantly in-channel-three "channel-three")

So now we have 3 channels that will randomly have their name pushed onto them we now need to do something with them. For the sake of simplicity lets assume all we need to do is log the result. We could write 3 distinct go loops (or suitably abstract it into a reusable function),

(go (loop []

(println (<! in-channel-one))

(recur)))

(go (loop []

(println (<! in-channel-two))

(recur)))

(go (loop []

(println (<! in-channel-three))

(recur)))

But regardles of how much you abstract away the mechanics you are still dealing with the 3 channels as 3 distinct entities when in many cases you should be dealing with a single channel derived from multiple sources. We achieve this with merge

(def merged (merge [in-channel-one

in-channel-two

in-channel-three]))

merged is now a channel that we can take from and recieve values from all 3 channels. Now we can perform our go loop over the single channel instead,

(go (loop []

(println (<! merged))

(recur)))

mix

merge is fine when you want to just grab a bunch of channels and treat them as one but sometimes this is not enough. When it comes to channels that produce effects visible to the user there is often a need to better control these messages. Imagine a chat application where each person is represented as a channel, or perhaps a log dashboard where each channel is a service in your system streaming log data.

In such situations, where the volume is high, there may be times you want to focus on a particular set of logs or chat messages, or surpress someone or something that is being particularly chatty. Maybe these messages can be discarded, maybe they are important and need to looked at later. These are the things that merge fails to address. These are the things that mix does address.

The key differences that set mix apart from merge are that,

- It introduces an intermediary component - the mixer

- It is configurable, you can add and remove input channels

- Channels can be muted, paused and solo'ed on demand

So lets take our 3 channels above and apply the abilities of mix to the situation.

First of all we need to create 2 things.

- The output channel - unlike

mergethis isn't created for us - The mixer - we create this via the

mixmethod

; manually declare our output channel

(def output-channel (chan))

; create a mixer linked to the output channel

(def mixer (mix output-channel))

We can also, at this point, set up our go loop for printing the data put onto the output channel

(go (loop []

(println (<! output-channel))

(recur)))

Unlike merge we still haven't declared what input channels should be associated with the mixer and ultimately output channel. We can do this using admix,

(admix mixer in-channel-one)

(admix mixer in-channel-two)

(admix mixer in-channel-three)

At this point we should start seeing stuff being logged to the console exactly like we did with merge. This is where mix starts to get interesting.

toggle

toggle allows you to control how the mixer responds to each input channel. You pass it a state map of channels and associated mixer properties. With toggle you can do any combination (though many would not make sense) of,

:mute- keep taking from the input channel but discard any taken values:pause- stop taking from the input channel:solo- listen only to this (and other:soloed channels). Whether or not the non-soloed channels are muted or paused can be controlled via thesolo-modemethod.

So lets imagine one of our mixed channels (in-channel-one) it getting a bit chatty. It could swamp our logging output and we might miss something important in another channel. We can use toggle to temporarily mute it,

(toggle mixer { in-channel-one { :mute true } })

Now our output will only be displaying the other 2 channels. But suppose the data coming in from channel one was actually important, as it stands muting a channel simply discards any takes that happen. If we want to stop taking anything from the channel (and therefore allow it to buffer on the channel) we can pause the channel instead.

(toggle mixer { in-channel-one { :mute false

:pause true } })

Finally if we want to only concern ourselves with channel one we can solo it

(toggle mixer { in-channel-one { :solo true } })

You'll notice I didn't set :pause back to false because soloed channels ignore their other properties..

Summing Up

We covered both the merge and mix methods of core.async. Both methods are higher level ways to combine and control multiple input channels into a single unified output channel.

merge offers a simple straigthforward way to combine channels but offers you little control after the fact. mix gives you greater control over the input channels and is exceptionally useful when you need to manage input streams.