The post has been updated to accomodate some of the excellent adivce from Roland Kuhn via his Gist

I've been playing around with Akka lately for a component I've been working on. The component, a simple remote file sychroniser will essentially batch download files from URLs returned by a remote API call. The specifics aren't important right now but thats the gist. The component is scheduled to run every 3 hours (using the Akka scheduler) but sometimes the entire download process can actually take longer than 3 hours and I don't want to end up thrashing the remote API for little benefit - so I wanted a fail safe to ensure a new download process would only start if the previous one had finished.

So I've got Akka and some kind of co-ordination requirement. There were 3 possible options,

- Make use of a global

var - Use Akkas FSM (Finite State Machine), or,

- Use an Actors

become&unbecomemethods

We'll start with some akka system boilerplate (with scheduler) and look at the options

// create the overarching actor system that will manage our application

val system = akka.actor.ActorSystem("devtracker")

// import our execution context

import system.dispatcher

// set up a scheduler to sync the registry

system.scheduler.schedule(0 millis, 3 hours) {

// try and start a download

}

Along with this we'll have an actor that performs the download and notifies something when it is finished.

The Global var

Simplest appraoch would be to just use a flag,

// create the overarching actor system that will manage our application

val system = akka.actor.ActorSystem("devtracker")

// import our execution context

import system.dispatcher

@volatile var isDownloading = false

// set up a scheduler to sync the registry

system.scheduler.schedule(0 millis, 3 hours) {

if(!isDownloading) {

system.actorOf(Props[Downloader]) ! Download

}

}

Then somewhere in our Downloader actor we'd set global isDownloading flag to true then, once the (synchronous) download process is complete, back to false again.

class Downloader extends Actor {

def receive = {

case Download => {

Application.isDownloading = true

// perform download

Application.isDownloading = false

}

}

}

Ugh mutable state, am I rite?!?. It's no fun having to manage shared mutable state (even if it is currently just only boolean flag). This is especially when you're using a system that aims to abstract away the concerns of concurrency.

Lets not forget that I've also broken the whole encapsulation of the actor model by explicity accessing Application and that just seems dirty. Of course you could keep refining this unitl you ended up with an actor that isolated the var and other actors passed messages via the Actor System (or its Event Bus) but, well, thats already kind of been done for us in Akka.

The Akka FSM (Finite State Machine)

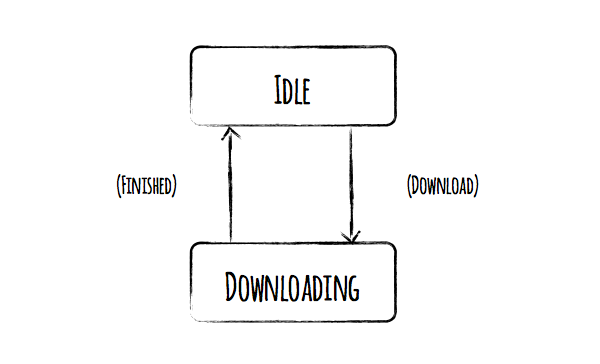

The rules we described above are pretty much describing a very basic state machine. The downloading component is either in an idle or downloading state and we can only initiate a download if the component is idling.

Akka provides a basic FSM implementation which is essentially an actor with a neat DSL for defining states and transitions. We can model our download case like so,

class DownloadCoordinator extends Actor with FSM[State, Unit] {

startWith(Idle, Unit)

when(Idle) {

case Event(Go, _) => goto(Downloading)

}

when(Downloading) {

case Event(Finish, _) => goto(Idle)

}

onTransition {

case Idle -> Downloading => {

context.actorOf(Props[Downloader]) ! Go

}

}

initialize()

}

The code above tells us that we have 2 states Idle and Downloading. When we receive a Go event (a simple case object) in the Idle state we move into the Downloading state. When we receive a Finish event in the Downloading state we go back to Idle.

Finally, on the transition of Idle to Downloading we tell our downloader actor to do its thing.

When the download completes our actor can simply tell it sender it is finished

class Downloader extends Actor {

def receive = {

case Go => {

// perform download

sender ! Finish

}

}

}

We don't need to directly tell the sender but here this is acceptable. The level of decoupling and indirection is entirely up to you.

Finally our scheduler simply asks the co-ordinator to Go

val coordinator = system.actorOf(Props[DownloadCoordinator])

system.scheduler.schedule(0 millis, 2 hours) {

coordinator ! Go

}

Now if the scheduler ticks while a download is active it just gets ignored (though you can optionally handle it in the whenUnhandled block of the FSM actor)

I'll come back this implementation near the end of the post.

Become/Unbecome

Do you find the FSM implmentation a bit wordy for something that only really has two states? There is a lot of extra stuff going compared to the boolean flag appraoch. Well actually actors are capable of being their own FSM without the need of the FSM trait.

Akkas Actors support a pattern of swapping out the actors message handler for another receiver via the become/unbecome methods. We can implement our download co-ordinator with alot les code like so.

class Downloader extends Actor {

import context._

def receive = {

case _ =>

become {

case _ => // do nothing

}

}

def download = future {

// perform download

unbecome

}

}

And thats it. This entire thing replaces both the co-ordinator actor and downloader actor. Our scheduler remains roughtly the same except we call this actor instead of our co-ordinator.

So whats happening? Well when we receive any message (for the first time for example) we call download which begins the download process. Then our actors becomes something else - the thing it becomes is a cold, uncaring machine - doing nothing to any message it gets. When the download completes the unbecome puts the actor back into its initial (idle) state.

Conclusion

So what did I personally end up using? I went with the FSM approach. Why? Well I think, even with the basic nature of our needs, the FSM approach is actually more understandable. Comparing my two solutions (which may or may not be good practise, I'm new to Akka) I find the become/unbecome approach to be rather cryptic - sure there are less lines to take in but thats a crappy metric to measure quality by. That said reaching for a fully fledged FSM strategy for every situation is probably going to grow out of control - so it may not always be the best case. Know thine weapons.